A brief critical analysis of appropriation and its digital resources.

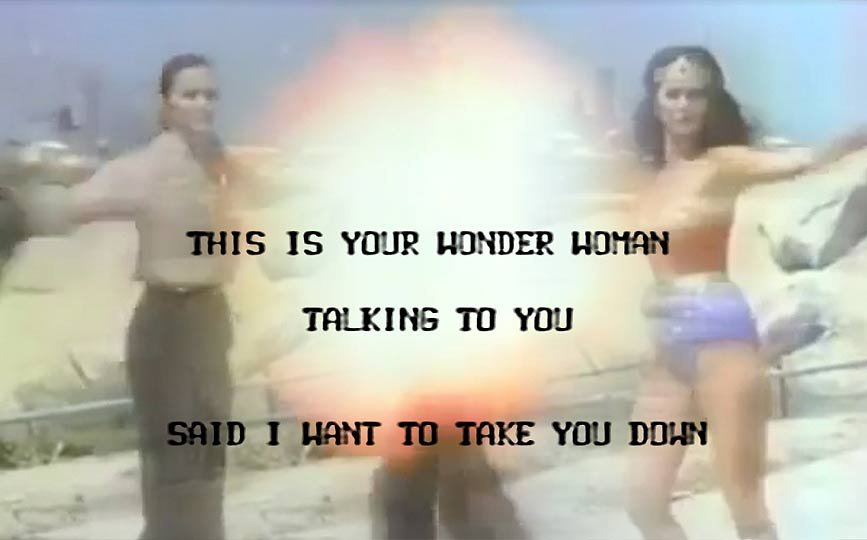

Appropriation has remained bound to art history through big names such as Leonardo da Vinci, Picasso, or Duchamp, who exemplify the consistent use of this technique/movement within the art world. With the so-called democratisation of technology, video art has consolidated its position as one of the key artistic disciplines of our time. As will be the case with many other forms of expression within the visual arts, appropriation has become one of the most frequent methods of producing pieces of video art. One of the first pieces of video art that employed this technique – Technology, Transformation: Wonder Woman – was created at the end of the 1970s by Dara Bimbaum, who used images from the TV series Wonder Woman to create a series of work which critiqued the role of mass media in the composition of roles that were almost always sexist.

A concrete example of appropriation in video art is found footage, which is simply the videographic extension of the collage. Lev Manovich defined this in “The language of new media. The image in the digital era” as a moving collage of images that can be ‘cut and pasted’, given that today’s images are stored on computers. But how do they get to our computers, and in what condition? When finding images to use in a new creation, there are a multitude of options from a range of audiovisual sources. There are artists who digitise old family films or use footage of strangers, films they find at remote markets or in disused cellars, while others create rips from VHS or DVDs, using well-known films or jewels of the cinematic vanguard. But in this era of information, information overload, and disinformation, where to find specific images of a certain thing? Of course: Youtube.

Youtube has become an image database that all video artists use. Without too close an inspection of the copyright dilemma – of the origin of the images and their artistic or commercial use – Youtube is the reference point for an entire generation of video artists. This was explored in the exhibition “Ten years at the zoo” at LAS NAVES ESPAI D’INNOVACIÓ I CREACIÓ in Valencia in 2015, marking ten years since the first video was uploaded to Youtube, “Me at the zoo”.

But as I mentioned before, Youtube does maintain a corporate interest, attempting to impose limits on creative freedom and the artists themselves, even when these involve the dissemination of knowledge (evidenced by the closure of certain channels as a result of political pressure).

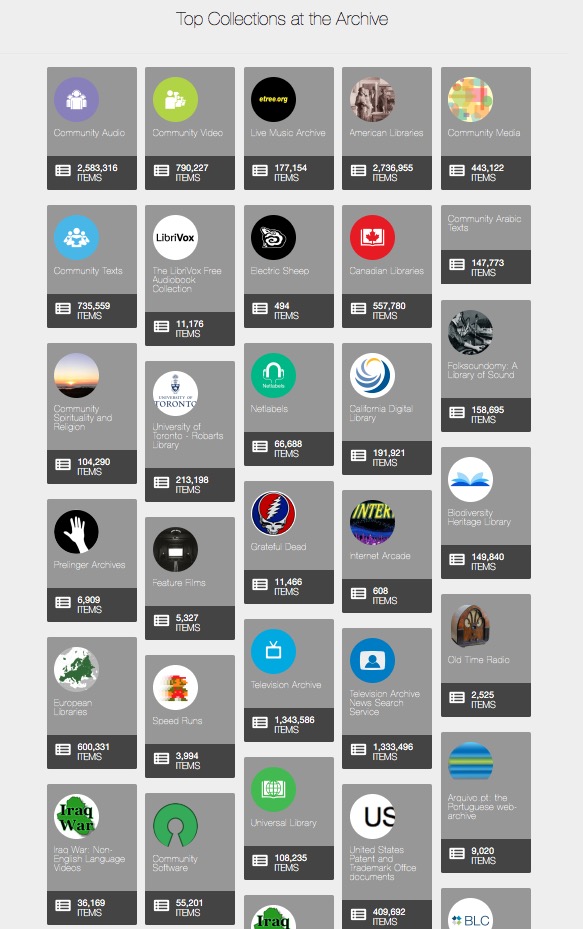

Archive.org was created to safeguard this spread of knowledge. It is run as a not-for-profit company and contains millions of videos, images, audio files, etc., some of which are licensed under creative commons while others’ copyright has expired according to the laws of the country in which they were created.

As a result, Archive.org has become one of the best multimedia libraries in the world. It shares a similar philosophy with Creative Commons, meaning that a panoply of image and audio banks have been created, such as FreedSound, OpenCulture or Videpong. For this reason, it has become an indispensable resource for many video artists. María Cañas (Sevilla, 1972), for example, describes herself as an ‘archive terrorist’, becoming one of the foremost proponents of appropriation in the international video art world through her videopatía and peculiar use of images. As well as serving as an example to renowned national libraries or public broadcasters – who have already begun digitising their content without always allowing for download – Archive.org means that we can continue to create with a quick visit to Google.